A Model Born in Disruption

The ultra-low-cost carrier (ULCC) was supposed to revolutionize air travel in the United States. Modeled loosely on Ryanair in Europe, ULCCs like Spirit, Frontier, and Allegiant promised rock-bottom base fares by unbundling every possible service: bags, seats, snacks, and even customer service. For a time, it worked. These carriers filled a niche that the legacy airlines had abandoned, especially on underserved leisure routes.

They transformed $49 fares into marketing magic and helped millions fly who might not have otherwise. They expanded to second-tier airports, played scheduling Tetris to maximize aircraft utilization, and embraced a revenue model that relied more on fees than fares. They took the low cost model pioneered by Southwest and took it to a new level.

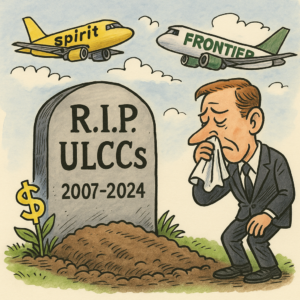

But in 2025, that model is crumbling. Spirit is flailing. Frontier is quietly repositioning. Allegiant is shrinking. And the broader market is moving on.

A Misguided Lifeline: The Judge and JetBlue-Spirit

In 2023, a federal judge blocked JetBlue’s proposed acquisition of Spirit Airlines, arguing that the merger would harm competition and eliminate one of the few remaining ultra-low-cost competitors. On paper, it was a classic antitrust argument: fewer airlines equals higher prices.

But the ruling failed to grasp a more nuanced—and more uncomfortable—truth: ULCCs aren’t dying because of consolidation. They’re dying because the ULCC model no longer works in the United States.

JetBlue’s planned takeover of Spirit wasn’t a hostile move to eliminate a competitor. It was an effort to salvage value from a struggling airline whose business model was increasingly incompatible with American consumer expectations, airport economics, and competitive dynamics.

The court, in trying to preserve theoretical competition, ended up dooming both carriers to strategic limbo. JetBlue, stripped of scale and gates, is drifting. Spirit, cut off from rescue, is flailing in a market that no longer tolerates its quirks.

ULCC Economics Are Broken

The fundamental promise of ULCCs—“you only pay for what you use”—has been overtaken by a consumer backlash. Passengers increasingly view unbundled pricing not as transparency, but as a bait-and-switch. A $39 fare becomes $129 by the time you add a carry-on and choose a seat. Carriers have increasingly learned to offer both bundled and unbundled fares at the same time.

In a world where Delta offers operational reliability and credit card perks, and legacy carriers have adopted more flexible fare structures, ULCCs struggle to justify their existence. The brand loyalty arms race—complete with co-branded credit cards, lounges, and status tiers—has left ULCCs behind. The ULCCs couldn’t be all things to all people.

Worse, ULCCs depend on ultra-high aircraft utilization, limited redundancy, and razor-thin margins. That makes them uniquely vulnerable to weather disruptions, ATC delays, labor shortages, and aircraft groundings. And guess what 2023–2025 delivered in abundance? All of the above.

Frontier has increasingly shifted toward routes with less frequency and higher fares. Allegiant is shrinking its network. Spirit? It has returned aircraft, paused growth, and is reportedly exploring bankruptcy once again, having previously filed and emerged in a prior restructuring.

Consumers Want Cheap—and Reliable

The early 2010s were fertile ground for ULCCs. The Great Recession made cost king. Legacy carriers were still clawing their way out of bankruptcy and consolidating. But in 2025, the priorities have shifted.

The ULCC pioneers were right, travelers do want choice. But travelers don’t just want cheap anymore. They want cheap and predictable. And ULCCs haven’t been able to deliver that. Flight delays, customer service complaints, lack of interline agreements, and no rebooking protections have all made flying Spirit or Frontier feel like rolling the dice.

In a post-pandemic world where flexibility, cleanliness, and support matter more than ever, the ULCCs’ “you’re on your own” ethos has worn thin.

The Market Voted—And It’s Voting No

To understand how we got here, it helps to look back to the rise and fall of People Express—arguably the first ULCC in America. Founded in 1981, it offered radically low fares and a no-frills approach that inspired both love and chaos. But its growth was too fast, and its infrastructure too brittle. By 1987, it was absorbed into Continental after financial turbulence made its model unsustainable. The echoes of People Express can be seen in Spirit and Frontier today: rapid growth, thin margins, and a promise of affordability that ultimately couldn’t scale.

FlightWisdom previously chronicled this history in detail in our piece “Remembering People Express, the First Ultra Low-Cost Carrier”. That article reflected on how People Express pioneered radically low fares and an unbundled model in the early 1980s—charging for everything from checked bags to in-flight snacks long before ULCCs became mainstream. It traced the airline’s rapid rise, its chaotic execution, and its eventual collapse into Continental by 1987. The piece remains a cautionary tale of how innovation without infrastructure can burn out fast—an echo increasingly familiar in today’s ULCC story.

ULCC market share peaked in the late 2010s and has since stagnated or declined. Investors have taken note. Spirit’s stock, once the darling of Wall Street entered bankruptcy, exited and is has plummeted again. Frontier’s parent company has shifted focus. Even Allegiant, which runs a hybrid ULCC model with less reliance on frequency and more on leisure destinations, has slowed expansion.

Compare that to the “Big Four” (Delta, American, United, Southwest), who now control over 80% of domestic capacity. They have embraced fare segmentation (Basic Economy, etc.) to offer ULCC-like pricing for those who want it, but with the operational reliability and brand recognition that budget airlines can’t replicate.

The ULCC model was a feature in a fragmented, pre-consolidation market. In today’s climate of loyalty, scale, and global alliances, it’s a bug.

What Could Have Saved ULCCs?

Could ULCCs have evolved to survive? Maybe. But they would’ve had to make painful trade-offs:

- Improve on-time performance and reduce cancellations (which requires spare aircraft and crews—costly!)

- Invest in customer service infrastructure

- Reduce complexity around fees and pricing transparency

- Partner with larger airlines to offer interlining or recovery options

In short, they would’ve needed to become more like the carriers they were trying to disrupt. But the economics never supported that shift. You can’t simultaneously be the cheapest and the most reliable. Something had to give. Even Southwest, the pioneer of low cost, has recently given up on anything that made it substantially different than their competitors.

A Judge’s Good Intentions, Poor Timing

The JetBlue-Spirit ruling was born of nostalgia and idealism. It imagined a world in which Spirit could remain an aggressive low-fare competitor. It ignored the financial distress and strategic dead-end the airline faced. It presumed that preserving the option of ultra-cheap fares was more important than acknowledging their viability.

The decision froze JetBlue in mid-transformation and left Spirit rudderless. It was, in effect, a regulatory act of CPR on a business model that was already brain dead.

The Future: Fare Fragmentation, Not ULCCs

If ULCCs are fading, what comes next?

The answer is already here. The legacy carriers have effectively absorbed the lessons of the ULCC era. Southwest has given up on its low cost ethos and become just another legacy carrier itself. Basic Economy fares provide price-sensitive options, while bundled fares allow you to get a predictable rate for all the classic amenities. Credit card rewards, upgrades, and operational consistency win hearts and wallets.

The new model isn’t fewer frills—it’s selective frills, layered across tiers, where you can pay more for exactly what you value, without being nickel-and-dimed into resentment.

Air travel in America has become stratified. You’re either chasing status with the majors, or you’re booking what’s cheapest on Google Flights and praying it runs on time. The ULCCs tried to live in that second category—and consumers are increasingly saying: “not worth it.”

It still survives in other parts of the world, but why? In Europe, regulations require airlines to compensate passengers when they are responsible for a delay. Even when they are not, it requires the airline to provide them with hotels, transportation, and refreshments. If the airline is required to take care of you, even if the flight failed to operate due weather, it changes the calculus. But even those airlines have softened their approach.

Conclusion: The Market Was Clearer Than the Court

The death of the ULCC in America wasn’t caused by mergers. It wasn’t regulatory sabotage. It was the collision of business model fragility and evolving consumer expectations.

A federal judge tried to hold back the tide by blocking JetBlue’s acquisition of Spirit. But the market kept moving. Now Spirit is teetering. JetBlue is disoriented. And consumers are gravitating toward airlines that offer something more than just the illusion of a good deal.

The ULCC era in America is over—not because no one wanted it, but because even those who did realized it wasn’t worth the cost.

The free-market jury has delivered its verdict. And not even a court order can overturn it.

Spirit Airlines filed for bankruptcy for the second time this year. As you may recall, Spirit had courted Frontier, and later JetBlue for an acquisition.…